Our growing collection of postcards from people’s summer research trips:

- Leipzig (Brianna Beehler)

- Petoskey and Ann Arbor, Mich. (Carly Goodman)

- London (Shaine Scarminach)

- South Bend, Ind. (William S. Cossen)

- Brussels and Northeastern Congo (Scott Ross)

- Frankfort, Ky. and San Marino, Calif. (Katrin Boniface)

- Washington, D.C. (Rebecca Graham Brenner)

- Lviv (John Vsetecka)

- Philadelphia (Bill Black)

Inside, cities burn. Soldiers plunder food and furniture. Shadowy figures wave, helpless, from windows in the distance.

Details from Plundering of Hubertusburg Castle in the Spring of 1761 (Bernd Baumbach, 2001). All photographs taken by Brianna Beehler.

These figures may appear strange. This is partly because they are miniatures, with an average height of 30mm, and partly because they are relatively flat, measuring only a millimeter or two in thickness. They are examples of zinnfiguren, or “tin figures,” which were widely produced in 18th- and 19th-century Germany and then exported abroad. Initially conceived as children’s toys, in the 20th century they became collectibles for adults, who would arrange them into large, meticulous dioramas based on historical events, sometimes containing hundreds or even thousands of figures.

Section of The Battle at Kolin on June 18, 1757, during the Seven Years’ War (Zinnfigurenfreunde Leipzig, 2006–7, figurines from the collection of Heinz Müller+, Halle, and supplements).

Detail from The “Minor War” (Bernd Baumbach, 1996).

My work on nineteenth-century toy culture led me to spend several weeks this summer traveling across Germany in search of zinnfiguren collections. Each collection is unique, not least because they all tend to include dioramas that focus on local historical battles and events. These photographs are from the Torhaus Dölitz in Leipzig, where I began my research trip.

Detail from The Battle at Hohenfriedberg (Striegau) on June 4th, 1745, during the Second Silesian War (Heinz Reh+, Penig, before 1968; restored by Zinnfigurenfreunde Leipzig).

While the dioramas do not exclusively depict battles, they do overwhelmingly recreate scenes of great violence, or the moments directly preceding or following brutal conflict.

Even in miniature—perhaps, indeed, because of it—the terrible scale of past wars is devastating. Tiny figures locked in endless battles. Looking down from a bird’s-eye view gives the impression of distance from these past events as well as a sense of immersion in their vast, unfolding presence.

Detail from The “Minor War” (Bernd Baumbach, 1996).

Detail from Napoleon and His Staff at Quandt’s Tobacco Mill, October 18, 1813 (Karl Stemmler, 1965).

Outside the Torhaus Dölitz, the dirt roads are shaded and empty, and horses graze.

Brianna Beehler (@briannabeehler) is a PhD candidate at the University of Southern California, where she is researching the cultural and mourning practices which emerged around dolls in nineteenth-century Britain.

Petoskey and Ann Arbor, Michigan

All photos by Carly Goodman.

The architect of the contemporary anti-immigration movement comes from Petoskey, a tiny resort town on the northern edge of Michigan. John Tanton, who died this summer, was an eye doctor whose vision extended far beyond his patients and his small town. He was an environmentalist and activist whose interest in conservation eventually morphed into advocacy for population control, abortion, eugenics, and immigration restriction. He founded the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), Center for Immigration Studies (CIS), U.S. English, and a long list of the most effective restrictionist organizations operating in the past 40 years. These organizations have helped frame the immigration debate, providing talking points, policy ideas, and a respectable face for an immensely violent and racist anti-immigrant ideology. Many alumni from his organizations staff the Trump administration.

Thanks to the generous support of the Bordin-Gillette Fellowship I was able to spend a week at the Bentley Historical Library in Ann Arbor, Michigan, researching in the unsealed portion of Tanton’s papers.

Tanton’s stationary featured a beehive. He was a beekeeper in his spare time, and often sent jars of honey to his correspondents and friends in town.

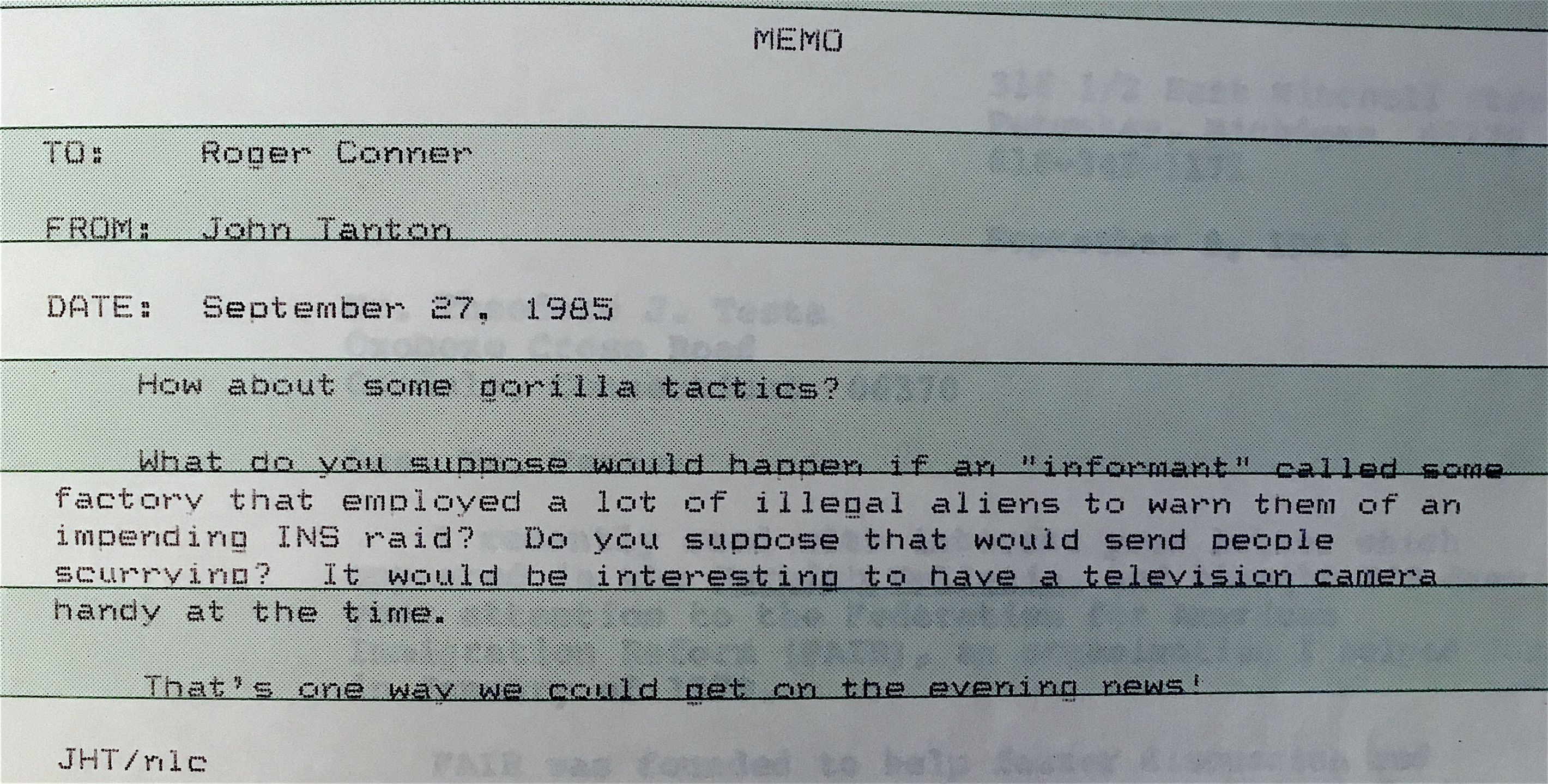

Among his papers was a 1985 memo suggesting the threat of an INS workplace raid would terrify immigrant workers, creating a politically useful image for the “evening news.”

On my last day in Michigan, I drove four hours north to Tanton’s home town, just days after his passing. Though its numbers swell during the tourist season, Petoskey’s year-round population is under 6,000. Boasting the motto “Light of the North,” the town has a cute downtown with fresh flower pots, and a breezy waterfront with lots of boats, walking trails, and a lighthouse (Tanton loved lighthouses, which is perhaps fitting for an ophthalmologist). Nearly the whole town is white.

Little Traverse Historical Museum.

The tranquility of the place—and the seeming gentleness of Tanton’s life there —is at stark odds with the white nationalist ideas he helped bring to U.S. immigration policy, about the waning birthrates of whites, the specter of an immigrant “invasion,” and the superiority of white, “Western” civilization.

Carly Goodman (@car1ygoodman) is a visiting assistant professor at La Salle University. She is working on a book about the contemporary immigration restrictionist movement launched by John Tanton.

In the song “Barracuda” from his 1974 album Fear, John Cale sings an ominous refrain: “The ocean will have us all.” Not exactly the most reassuring sonic backdrop for a 3,500-mile flight over the Atlantic Ocean. Yet I found myself listening to Cale’s Welsh burr in early August as I traveled to England for a research trip to The National Archives (TNA).

Prior to my visit, I had only heard good things about TNA. But I still began the trip with some trepidation. My research often takes me to government archives, and the experience can be less than ideal. Reticent staff, opaque procedures, and a chilly atmosphere are not uncommon. Thankfully, my visit to TNA was the exact opposite.

Staying near London’s center, I took a breezy tube ride out to Kew each day to visit the archives. The process for requesting materials is essentially automated, so I could work at my own pace and conserve energy. All the better, since I generally find archival research mentally exhausting; I sometimes liken it to spending eight hours looking for lost keys. With a vague sense of what you’re after, you work under mild strain for indeterminate periods, only to arrive at sudden moments of relief and revelation.

At the same time, archival research also entails its own curious form of embodiment. Sitting in the same position performing repetitive motions all day can pull you into your body in unexpected ways. My terrible posture suddenly becomes an acute concern. Silence, even when not expected, must be preserved at all cost. The general lack of drama makes simple movements seem, well—dramatic.

Historical research can also be unavoidably voyeuristic. I sometimes feel like a member of the Greek chorus, standing silently offstage full of hidden secrets about the action unfolding on the page. During one of my days at TNA, I came across a memo from an official in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The official had received a report from his US counterpart about a conference they both attended, though he didn’t reciprocate the gesture. He wrote to his superiors that the British government had no policy to do so, adding: “I imagine they prepare confidential reports and papers on the sessions which they do not volunteer to us!” Having seen the corresponding records in US archives, I could readily confirm.

Historical research can also be unavoidably voyeuristic. I sometimes feel like a member of the Greek chorus, standing silently offstage full of hidden secrets about the action unfolding on the page. During one of my days at TNA, I came across a memo from an official in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The official had received a report from his US counterpart about a conference they both attended, though he didn’t reciprocate the gesture. He wrote to his superiors that the British government had no policy to do so, adding: “I imagine they prepare confidential reports and papers on the sessions which they do not volunteer to us!” Having seen the corresponding records in US archives, I could readily confirm.

After assuming the archive routine, it can be easy to forget the outside world. A strike at Heathrow Airport, called off at the last minute, almost extended my stay. A visit to the Tate Modern one evening was canceled after a bizarre incident in which a six-year-old French boy was thrown from the museum’s tower. (The boy survived the five-story fall, and the teenager who threw him has been charged with attempted murder.) And shortly thereafter the trip was over. I had to pack my things and go, still thinking of all those boxes I needed to go through.

Shaine Scarminach (@sascarminach) is a PhD candidate in history at the University of Connecticut, where is he writing a dissertation on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

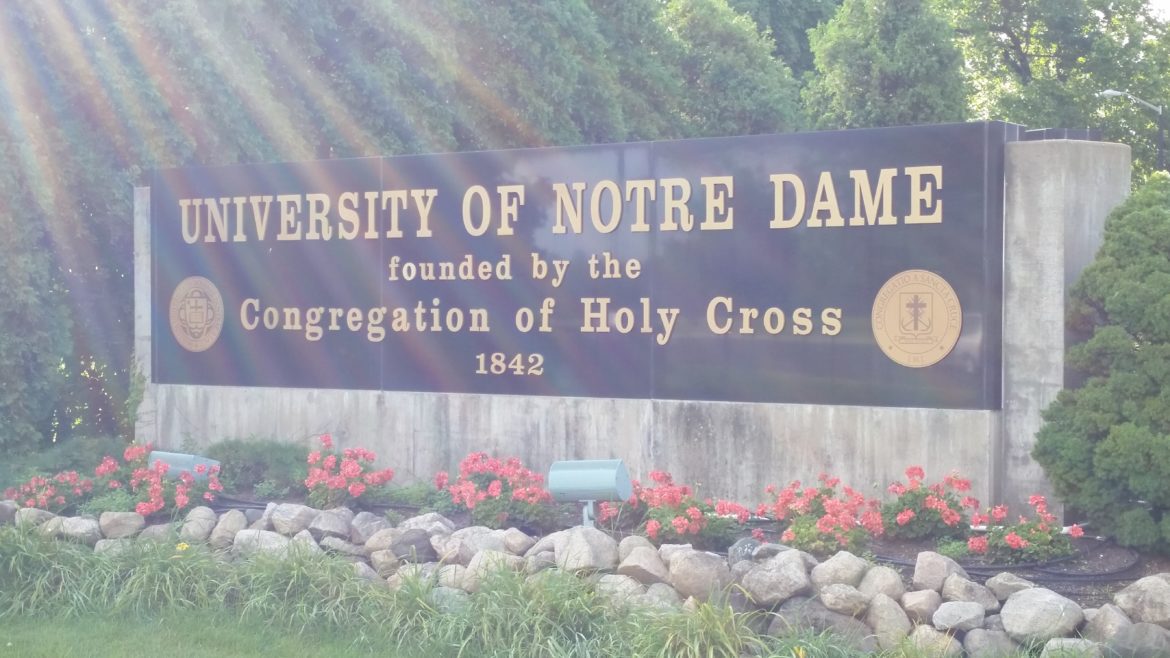

I was honored to receive a research travel grant this year from the University of Notre Dame’s Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism. It was my second time researching at Notre Dame, having received another Cushwa Grant for my dissertation research in 2013; this time I was working on a future book project about lived religion among Catholic soldiers in the Civil War.

Most exciting for me was being able to work at an institution that is actually a major subject of this research project. Notre Dame sent several chaplains, students, and alumni to serve in the Union Army during the war, so researching these individuals at the location where they lived and worked was a particular privilege.

I worked for a week at the University of Notre Dame Archives, which are housed in the Theodore Hesburgh Library. The library is named for the Holy Cross priest who served as the university’s president from 1952 to 1987.

Hesburgh Library is an impressive building adorned with an enormous mural, The Word of Life, known popularly as “Touchdown Jesus.” The position of Christ’s arms in the photograph below should explain the nickname.

Jesus’s positioning in the mural is not the only reason for the “Touchdown” nickname. The mural faces the Knute Rockne Gate of Notre Dame Stadium, a storied location in university and college football history.

I completed much of my work in the first-floor reading room, although I also spent significant time performing microfilm research in the basement and in the library’s sixth-floor special collections reading room (where I worked during my previous visit six years ago).

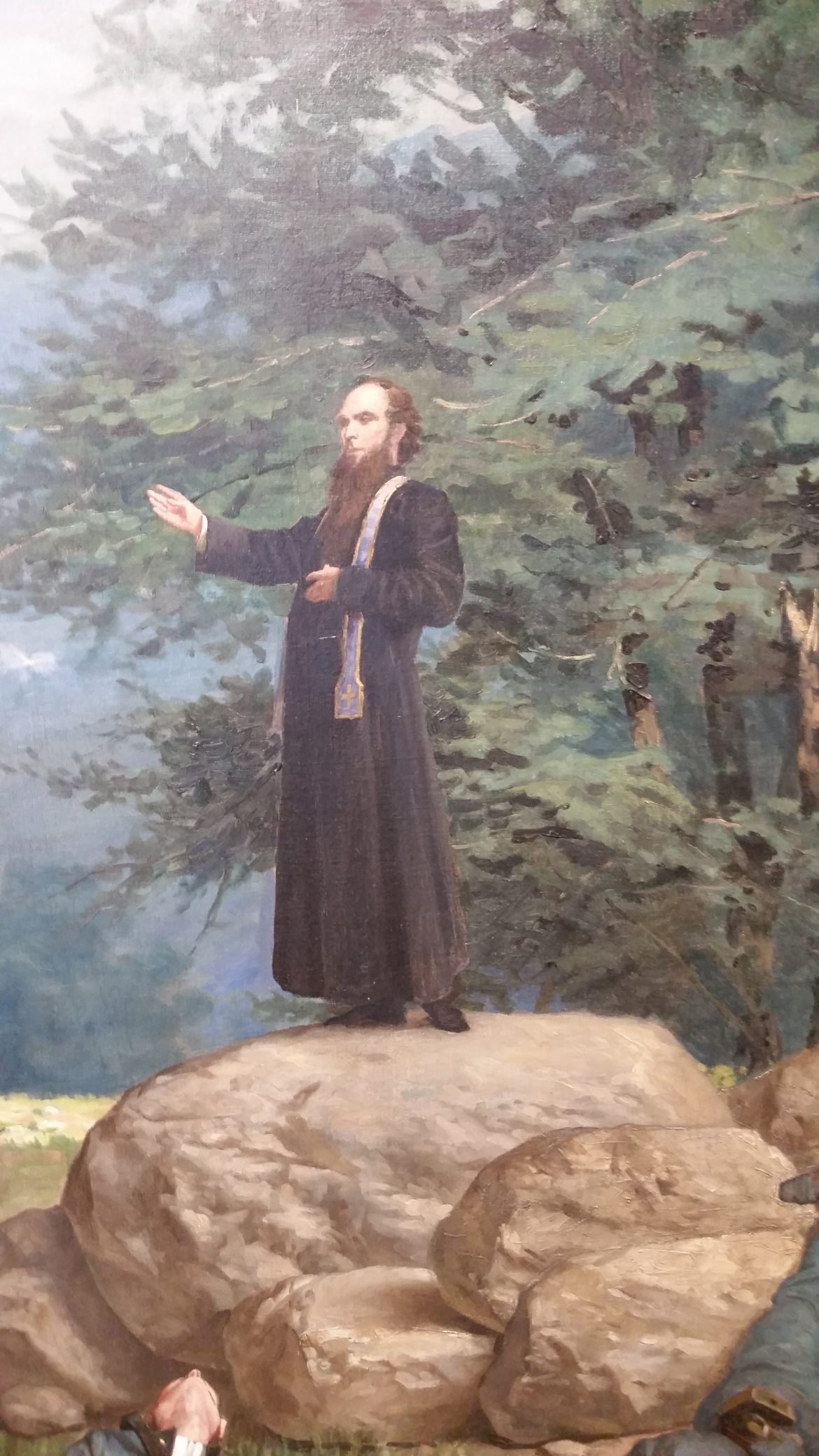

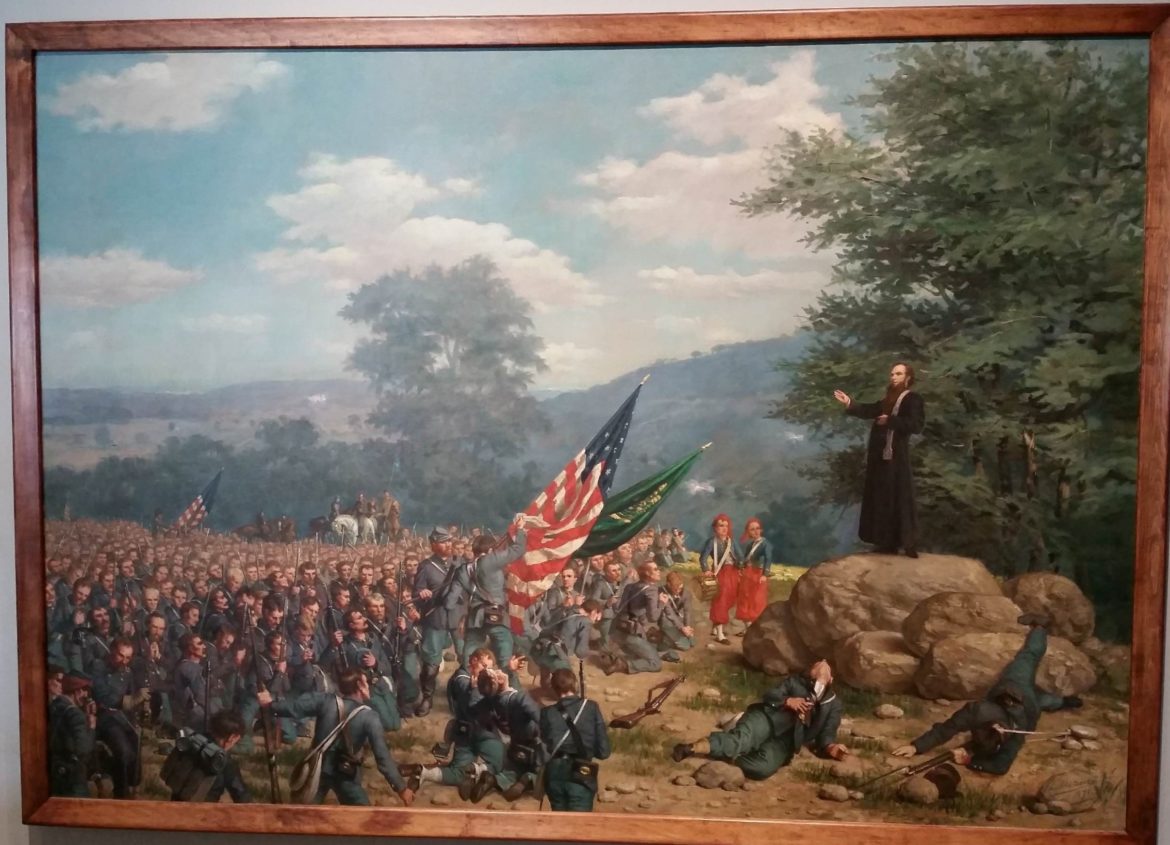

For those studying Civil War Catholicism, Rev. William Corby, a Holy Cross chaplain in the Union’s Irish Brigade who served on two separate occasions as Notre Dame’s president, becomes a familiar figure. Corby became well known for performing a general absolution for assembled Union soldiers during the Battle of Gettysburg. Father Corby’s sacramental feat is commemorated today on the battlefield with a statue depicting his absolution. As I planned my trip to Notre Dame, I was excited to have the opportunity to view at the university’s Snite Museum of Art a wonderful painting of the event by Paul Wood, who created the piece when he was just nineteen years old and a year before his untimely death. For an excellent analysis of Wood’s painting, I recommend Andrew Mach’s 2015 essay at the Religion in American History blog.

Paul Wood, Absolution Under Fire (1891), Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame.

Another statue of Father Corby absolving the soldiers also appears on Notre Dame’s campus. It stands outside the recently demolished Corby Hall and is presently on the edge of an active construction site.

While Father Corby now appears to be blessing heavy machinery, this statue and the Wood painting are visual evidence of the strong links between Notre Dame and lived Civil War Catholicism. I unfortunately did not have time to pay a visit to Father Corby’s burial site on campus, but I plan to talk a walk to his gravesite when I return to campus next year for another week of work – the divided research trip is a necessity for a full-time high school teacher with limited space for travel during the school year.

This research trip was altogether one of the most productive and personally satisfying of my academic career. The insights into soldiers’ lived religious experiences I gained from the papers of various Catholic chaplains and officers were invaluable, and I even had a chance to perform some additional archival work for my current book project, which was built largely on the research I completed during my first Notre Dame trip when I was in graduate school! I cannot recommend strongly enough taking a research trip to the Notre Dame Archives. It is an essential stop for scholars of Catholicism at a university significant in its own right in American religious history.

William S. Cossen (@WilliamCossen) received a PhD in history from Pennsylvania State University and teaches at the Gwinnett School of Mathematics, Science, and Technology near Atlanta. He is currently writing a book about American Catholics and religious nationalism in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.

Belgium and Northeastern Congo

Northeastern Congo is made up of rural communities with poor roads and even poorer cellular service. My research in Haut Uele province focuses on its modern humanitarian infrastructures—two-way radio networks that non-governmental organizations have built in an effort to connect communities—but it also concerns the longer history of infrastructure, remoteness, and connection in the region.

Africanist historians must often split research time in Africa with visits to the former imperial metropoles—a month in Senegal and a month in France, several weeks in Mozambique and several more in Portugal—and the experience can play bizarre tricks with your sense of space and time. Since Congo was once a colony of Belgium, I spent time in three different Belgian archives: the African Archives in Brussels, the Royal Central Africa Museum in Tervuren, and the KADOC Documentation Center for Religion and Culture in Leuven.

When visiting these archives, the violent and extractive history of Belgium’s presence in the Congo was impossible to ignore. The museum in Tervuren is housed within an ornate neoclassical palace, still decorated with racist statues despite recent multimillion-euro renovations, and was first established to showcase King Leopold II’s colonial ambitions at the 1897 International Exposition, including three “exhibits” of Congolese villagers. The archives sit in what was the Welcome Center for African Personnel (Centre d’accueil pour le personnel africain, CAPA) during the 1958 World’s Fair.

The CAPA Building holds the archival service of the Royal Museum for Central Africa. All photos by Scott Ross.

Among their files, I found an assortment of artifacts from government reports to colonial officer letters to missionary accounts, all of which I look at from the vantage point of my months of fieldwork in Haut Uele.

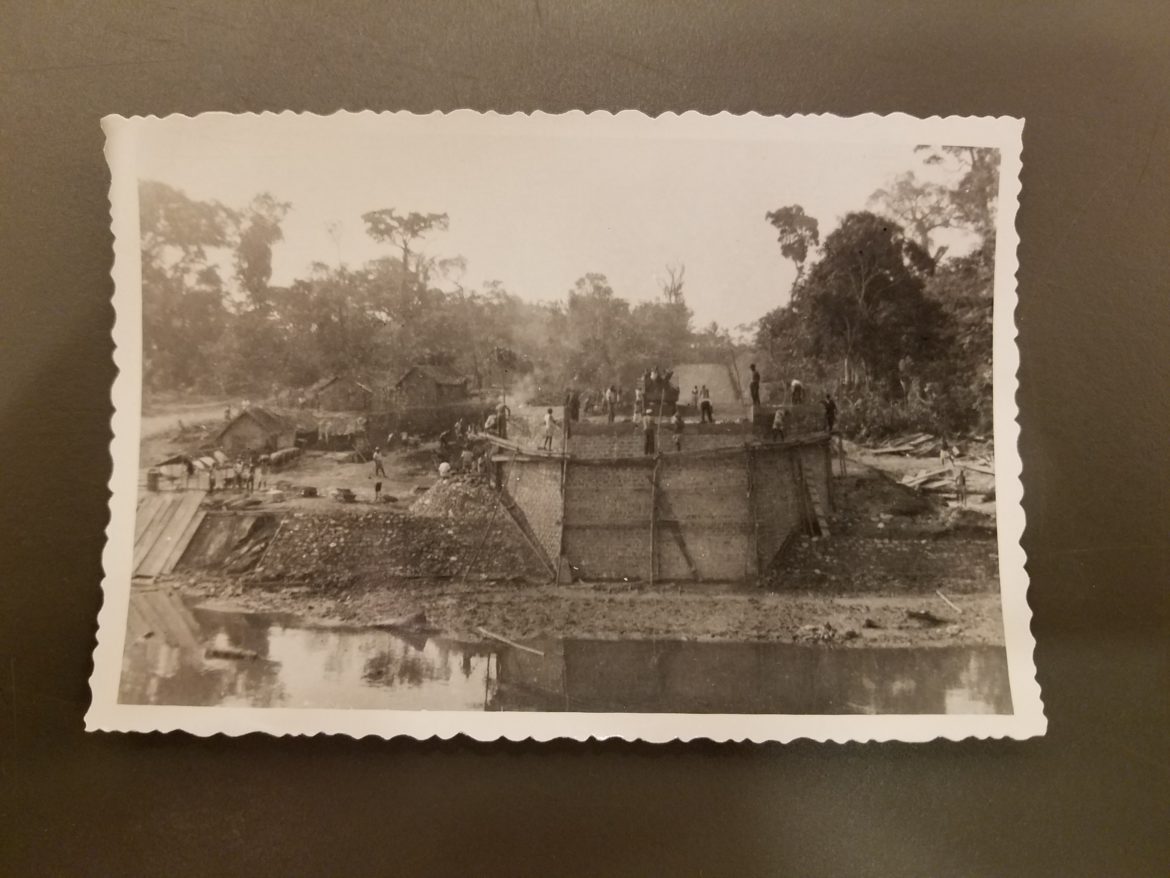

For example, when I traveled to the town of Niangara to conduct interviews, I found a town whose heyday had long passed, with the remains of large colonial and Mobutu-era buildings in disrepair, while the bridge over the River Uele had been recently renovated by Indonesian engineers in tandem with the MONUSCO peacekeeping force. Back in Brussels, I found a series of photographs from the initial construction and grand opening of that same bridge (I had been looking for the history of another bridge, in the town of Dungu, but my infrastructural interest chased everything). Niangara has gone through many changes in the intervening years, but the bridge and its link to foreign investment and interest endures.

The construction of the bridge over the Uele River in Niangara, 1950. From “Transports par route.” AA PD(1637).

The same bridge, recently rehabilitated by MONUSCO.

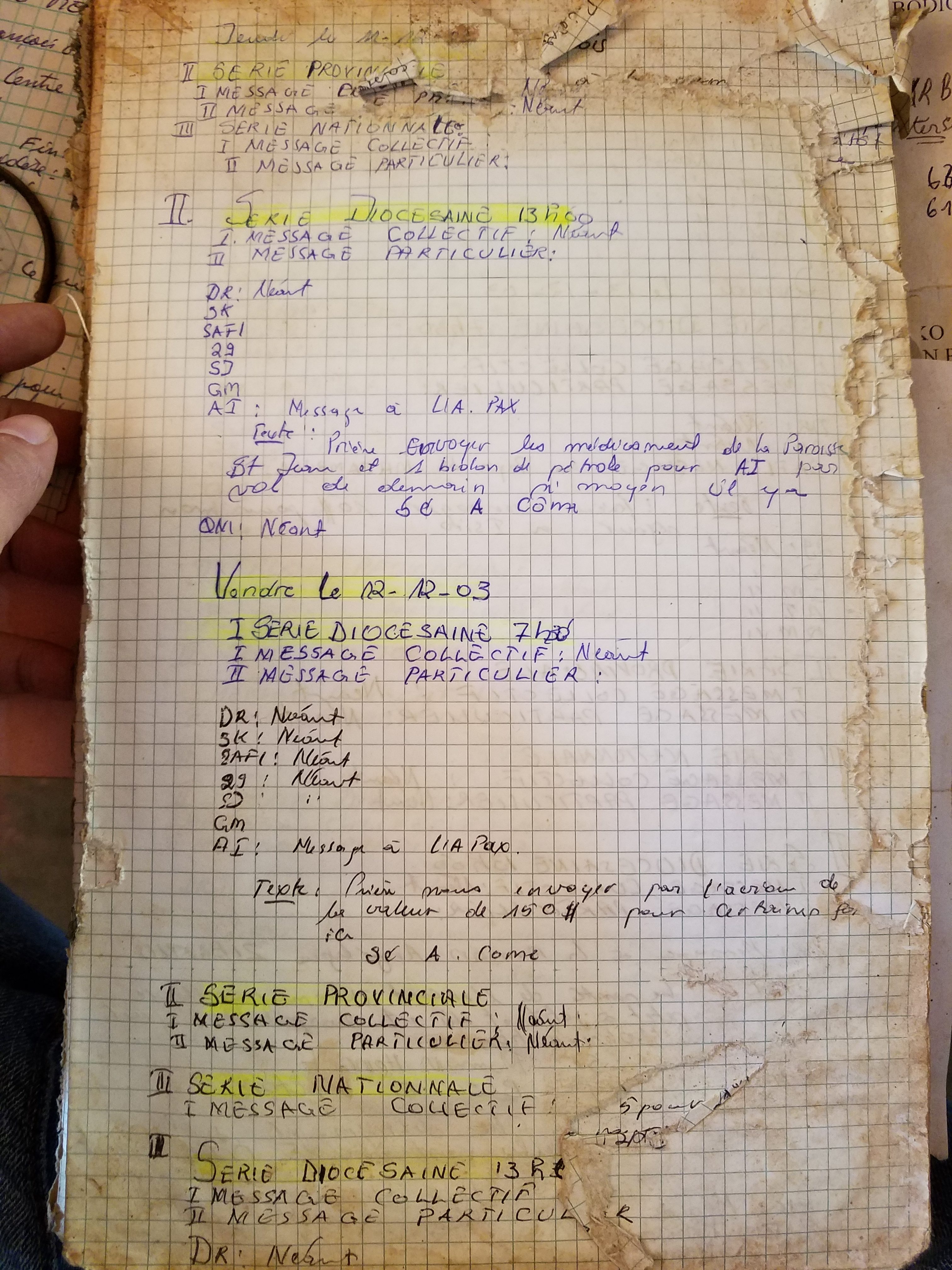

These colonial archives also complement my own local archival work. The humanitarian radios that I study were modeled on an existing radio network operated by the Roman Catholic Church in the region, where parishes would share information about expenses and inventories. When the Ugandan Lord’s Resistance Army began carrying out attacks in the area in 2008, operators used these church radios to track incidents, casualties, and rebel movements.

These books hearken back to the missionary notes found in the Leuven archive, where the collections include the daily reports and requests of various Catholic missions across the region. The missionary presence in Congo was one of the ways that the Belgian metropole found its hold in the rural hinterland, funding health centers and schools across the colony.

Radiophonie notebooks listing daily news, Dungu.

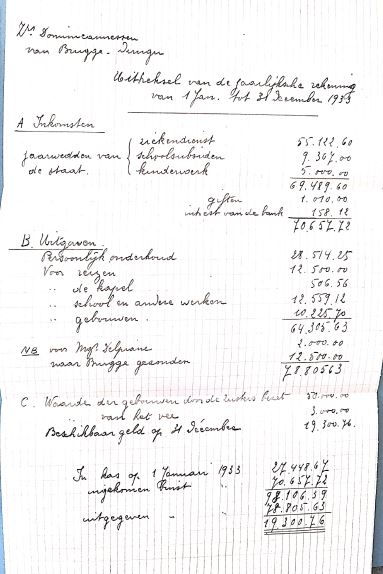

Annual accounts of the mission in Dungu, 1933. From “Jaarrekeningen van de missiepost Dungu (1930-1939)”, KADOC BE/942855/558.

As I arrive back in Haut Uele and look through my notes from the archives, I continue to find little connections. The small shuttered shop across the street from my house bears a Greek trader’s name, Coutsoukous, and the same name appeared in a 1960s business directory. I watch my interlocutors install antennas for their radio network, and I recall government reports about the expansion of its predecessor, the wireless telegram. As people navigate tensions with pastoralists who have come to the region, supposedly from Chad or Cameroon, I remember letters from missionaries and colonial officers about the efforts to monitor the porous border with Sudan. The people around me may talk of working to make the rural Congolese more connected to one another and the outside world via radio, but the historical reality is that the region sits at a crossroads that has been connected in other ways before—with varying consequences.

Scott Ross (@scott_a_ross) is a PhD candidate in anthropology at George Washington University, where he is researching a radio early warning network in northeastern Congo, which he frames within larger questions about the infrastructure of humanitarian intervention.

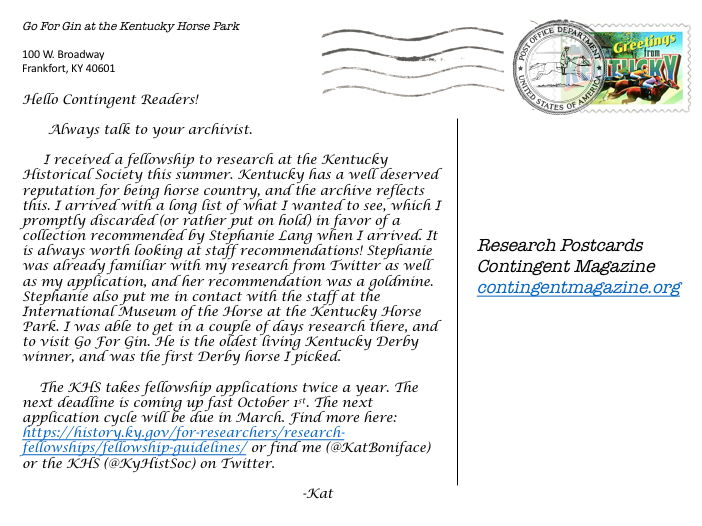

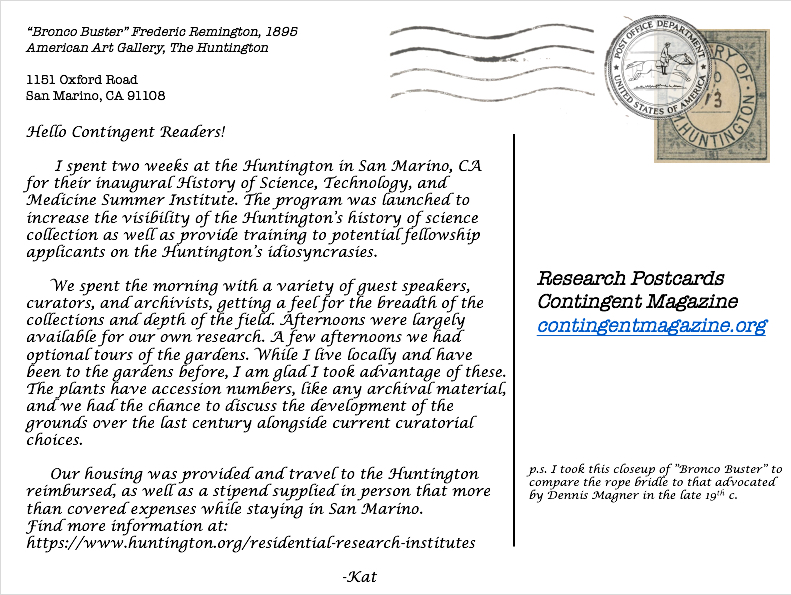

Frankfort, Kentucky and San Marino, California

Katrin Boniface (@KatBoniface) is a PhD student in history at the University of California, Riverside, where she is researching modern horse breeding and its relationship to evolutionary and genetic science.

Greetings from the Smithsonian National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C. I came here to research material culture relating to my dissertation on religion-state relations through the lens of Sunday mail delivery; I mostly looked at objects from the late-nineteenth century. The Railway Mail Service badges from 1898 and 1899 made the postal carriers and clerks that I read about in other archives seem more real.

Rebecca Graham Brenner (@TheOtherRBG) is a PhD candidate in history at American University in Washington, DC.

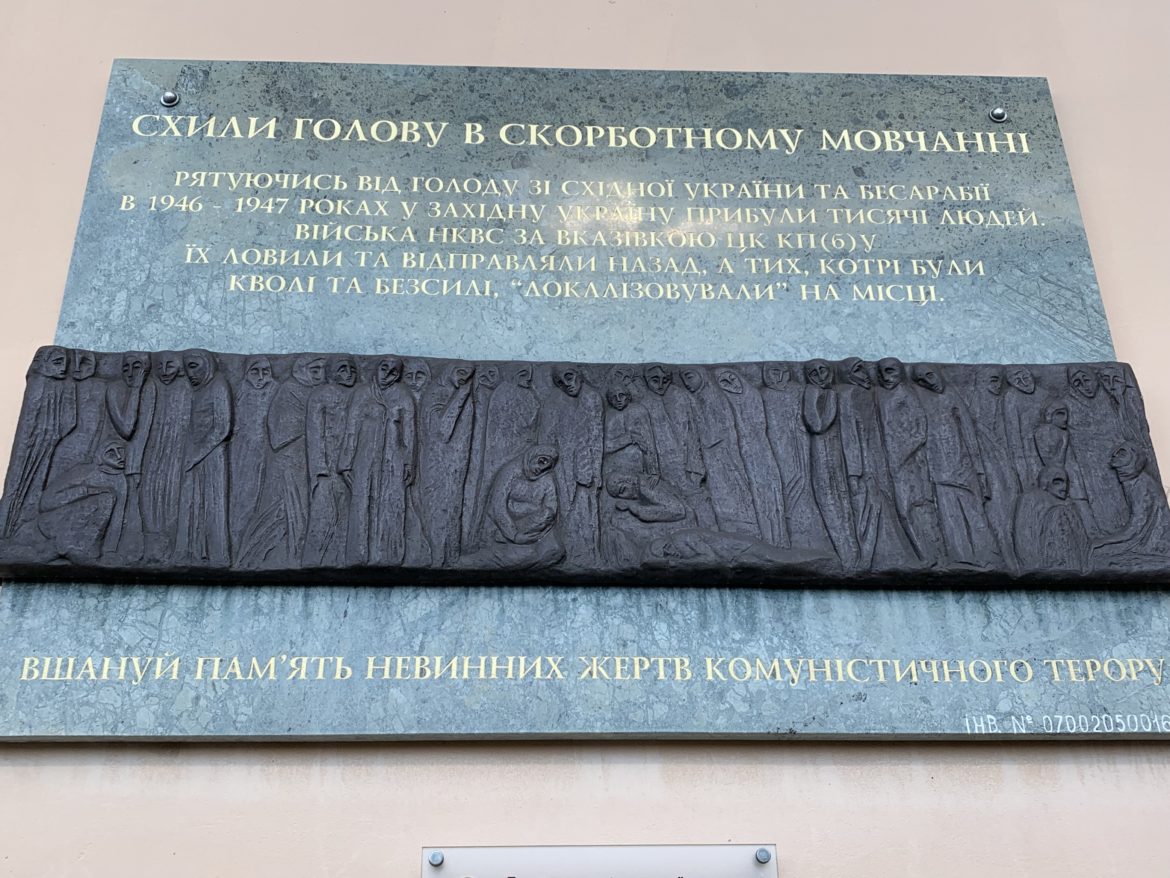

The Pidzamche train station. Thousands of people came here in the spring of 1947, attempting to flee famine in eastern and central Ukraine. They were met by station employees and officers of the NKVD, the Soviet secret police.

A plaque hangs on the side of the Pidzamche station commemorating the 1946–47 famine and the atrocities committed by the NKVD. In 2005, an excavation on the side of the station found a mass grave with the remains of nearly 500 people. The former mass grave is now a newly-paved parking lot.

A sign marking the “Victims of Communist Repression and Holodomor” at the Lychakiv cemetery. The remains of those found at Pidzamche were reburied here in 2009 in an underground crypt.

Large crosses, marking the Pidzamche victims reburied at Lychakiv, loom over the graves of soldiers killed in eastern Ukraine during the recent war with Russia.

John Vsetecka (@JohnVsetecka) is a PhD student in history at Michigan State University, where he is researching the Holodomor famine-genocide in Ukraine and its aftermath.

This is actually from August 2016, the week after the Democratic National Convention, when I spent a week at the Presbyterian Historical Society. I was mainly there to learn how the Presbyterian press covered the 1906 merger of the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A. (the “Northern” Presbyterians) with the Cumberland Presbyterians, who were predominantly in the upper South and lower Midwest.

It was a family trip. The boys, both under two years old and accustomed to Central Standard Time, would wake up early each morning, so we would explore the neighborhood we were staying at (East Passyunk) for a couple of hours before the archive opened.

The music is from “Appalachian Grove I” (via Internet Archive, licensed under CC BY-ND 3.0) by Laurie Spiegel, a pioneer of electronic music who developed the Music Mouse software program.